Curious Kids is a series for children of all ages. If you have a question you’d like an expert to answer, send it to [email protected].

Are there any planets outside of our solar system? – Eli W., age 8, Baton Rouge, Louisiana

This is a question that human beings have wondered about for thousands of years.

Here’s how the ancient Greek mathematician Metrodorus (400-350 B.C.) put it: A universe where Earth is “the only world,” he said, is about as believable as a “large field containing a single stalk.”

About 2,000 years later, in the 16th century, the Italian philosopher Giordano Bruno suggested something similar.

“Countless suns and countless earths” existed elsewhere, he said, all rotating “round their suns in exactly the same way as the planets of our system.”

Scientists now know that both Metrodorus and Bruno were essentially correct. Today, astronomers like me are still exploring this question, using new tools.

The exoplanets

There is now evidence that demonstrates the existence of “exoplanets” – that is, planets orbiting stars other than our Sun.

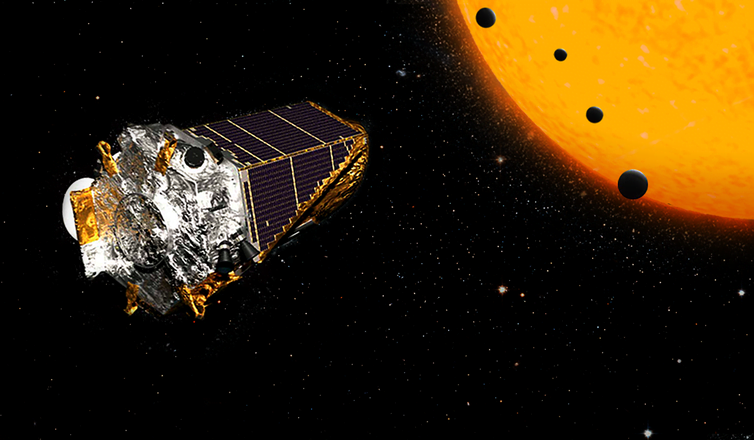

That evidence is based on the discoveries made by the Kepler space telescope, launched by NASA in 2009.

For four years, the telescope stared continuously at a single region of space within the constellation Cygnus.

Looking from Earth, it’s an area that takes up less than 1% of your view of the sky.

How the telescope worked

Kepler had 42 cameras on board, similar to the kind of smartphone camera that you use to take pictures. In that one region, the telescope detected more than 150,000 stars.

About every half-hour it observed the amount of light radiating from each star. Back here on Earth, a team of Kepler scientists analyzed the data.

For most stars, the amount of light stayed pretty much the same.

But for about 3,000 stars, the amount of light repeatedly decreased, by small amounts and for several hours. These drops in brightness happened at regular intervals, like clockwork.

The drops, astronomers concluded, were caused by a planet orbiting its star, periodically blocking some of the light that Kepler’s cameras would otherwise detect.

This event – when a planet passes between a star and its observer – is known as a transit.

And that means that in that one speck of space the Kepler telescope found 3,000 planets.

That’s only the beginning

Although 3,000 planets sounds like a lot, it’s certain many others within that area remain undetected.

That’s because their orbits never blocked the light as seen by Kepler. After all, planetary orbits aren’t all the same; they’re randomly oriented.

But because of the number of transits observed by Kepler, and astronomers’ knowledge of geometry, we can make a good guess on the total number of exoplanets out there.

And after making those calculations, scientists now think, on average, that every star has at least one planet.

This discovery has revolutionized astronomy and our view of the universe.

100 billion stars, 100 billion planets

For instance, our Milky Way galaxy has at least 100 billion stars; that means it has at least 100 billion planets too.

But remember: The universe holds up to 2 trillion galaxies. That’s 2,000,000,000,000! And each galaxy contains tens or even hundreds of billions of stars.

So the number of planets in the universe is truly astronomical, roughly equivalent to the number of grains of dry sand on every beach on Earth.

Some of those planets are gas giants, like Jupiter in our solar system. Others are boiling hot, like Venus. Others may be water worlds or ice planets. And some are Earth-like.

In fact, the Kepler team calculated the abundance of Earth-like planets in the “habitable zone,” a sector of space around each star where a world might have moderate temperatures and liquid water.

They found approximately 50% of Sun-like stars in the Milky Way host an Earth-like planet in the habitable zone.

That adds up to billions of potentially habitable worlds just in our galaxy.

Could life exist elsewhere?

Although scientists haven’t found proof yet, many – including me – now think it’s unlikely that Earth is the only planet where life evolved. That would be as surprising as a large field containing a single stalk.

When will humans detect life elsewhere? Will it be intelligent life? Will people ever receive a message from another civilization?

Today, hundreds of scientists around the world are trying to answer those questions.

Hello, curious kids! Do you have a question you’d like an expert to answer? Ask an adult to send your question to [email protected].

Please tell us your name, age and the city where you live.

And since curiosity has no age limit – adults, let us know what you’re wondering, too. We won’t be able to answer every question, but we will do our best.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Jean-Luc Margot is a UCLA professor with joint appointments in the Department of Earth, Planetary, and Space Sciences and the Department of Physics and Astronomy. He is a planetary astronomer who conducts research on the properties of planetary bodies with a variety of spacecraft and telescopes. His research interests include the dynamics and geophysics of planetary bodies, radio and radar astronomy, and SETI.