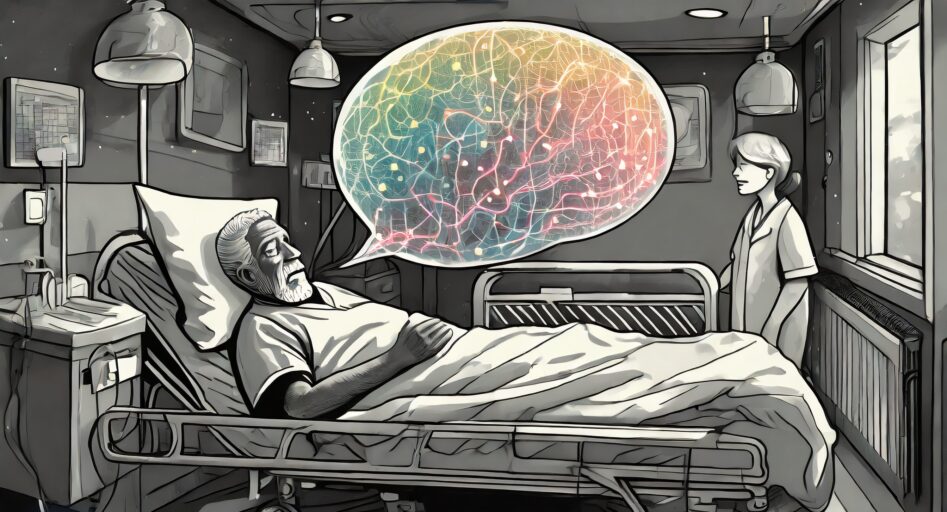

“Baby Girl,” Papa said. He opened his eyes four days after falling into a coma and thirty-two minutes before dying. Papa’s blood disease had taken his health and had led to a loss of lucidity, though the doctors didn’t know why.

But now he knew me. I asked the hospice nurse to call Mama. She would be furious that she had gone home to rest and missed his waking.

“Papa,” I said and kissed him on the cheek.

“You were right, Baby Girl. It is mechanical.”

I didn’t know what Papa was talking about, but I didn’t care. How I had missed the rumbling love and kindness emerging from his voice.

“What’s mechanical, Papa?” I asked.

“What you said. The neurons,” he replied.

Neurons? Then I remembered. Back in my first year of graduate school, I went home for winter break. As always, my parents asked me to brief them on the latest advances in physics. It was a joke because Papa was, as he put it, “a simple mailman.” He claimed he would comprehend the wonders of physics if someone could only explain them. For Mama, physics was a crazy science based on thought, not reality. All she cared about was whether I would land a professorship. But they pretended to understand my work and often asked questions to show interest.

That winter break I told them about a new physics theory that nerve signals sent from the brain were not just a voltage electrical pulse, but also a mechanical pulse. It was a complicated theory, and I know I didn’t explain it well.

Why Papa would remember this more than ten years later baffled me. Neurons weren’t even my current field of study. As an astrophysicist, my work focuses on the universe, not the brain. Papa was in his last throes of life, but I had to ask.

“Papa, what made you think of brain neurons? You know that’s not my area.”

“Not here, but it is there. You’re going to get the Nobel.” He nodded as vigorously as a dying man could.

“Where, Papa? Where is it my work?”

“You know . . . the multiverses,” he said. Papa understood that theory, at least the idea that the multiverse could exist, if not the why.

I smiled. In the dreams of his coma, my papa imagined alternate universes, alternate versions of me.

“So I’m studying the brain?”

“Yes, and I’m not sick, and you’re married, and I’m a grandfather, and your mother and I visit Venice, and you’ll get the Nobel.”

“That sounds nice.”

“It is.” He sounded lucid. It was all real to him.

“And you didn’t marry that lousy jerk, Ben. You married Antonio.”

When Papa and Ben had first met, they locked eyes on each other and the glares that emerged were molten enough to ignite a Hawaiian volcano. Later, I appreciated Papa’s hatred. Ben, disguised as the love of my life, turned out to be a soul-sucking leech that drained the heart. Papa saw through him right away. I didn’t. Ben kicked me around for three years before I acknowledged the hurt. But Antonio . . . I searched my memory.

The summer between my junior and senior year I went to Notre Dame to attend a special science program for undergraduates. Antonio was there for a summer residency as part of his master’s in fine arts. You’d think that physics and museum studies wouldn’t go well together, but we latched onto each other. He put a scarf around my neck and took me to art exhibits. I wrapped him in a white coat and showed him the science labs. We played Frisbee on the university greens, took hikes under the full moon, and ate at any ethnic restaurant we could find. We talked about everything, from politics and social decay to cloud shapes and what ants might think about. But at summer’s end I went back to Pennsylvania and he returned to California. We made the usual promises: “I’ll come see you.” “We’ll visit over Christmas.” It never happened. Instead, we exchanged phone calls and e-mails—until we didn’t. I hadn’t thought of him for years.

“Papa, are you sure it was Antonio?”

“Oh yes. He’s such a good father. Better than me, I guess.”

“No one’s better than you.”

Papa closed his eyes, and his breathing softened. As I watched his chest slowly go up and down, I tried hard to remember. Notre Dame’s summer program had prestige, but with a price tag to match, more than the cost of one year of tuition at my state university. No way would I have let my parents know I was goofing off. I was certain I had never told them about Antonio.

Papa’s breathing stopped and then resumed, stopped and then resumed. The hospice nurse lurked near the door, ready to come in when it was over.

Later, people wondered why I didn’t cry. After all, I had been such a mess during his illness. But why should I be sad? When he was diagnosed, I had cursed the shortness of time. Now I know there is endless time and endless possibility. He is somewhere else in Venice riding the gondola with my mother, somewhere else playing with his grandchildren. And here, my here, I took the leap and found Antonio again. I think of him as Papa’s last gift to me, at least in this world.

Mama arrived a few minutes after Papa died. She cried, angry with herself for missing his passing. She demanded that I tell her his last words. I swore they were of her. “He said he would love you for all time.” It wasn’t a complete lie. Somewhere—many somewheres—he does love her for all time, endless time. Still, here, that’s not what he said.

Seconds before he died, Papa opened his eyes. “Well, I didn’t expect that.” Then he smiled at me. “Baby Girl, you’re going to love it.”

And so I wait.

Edited by a Fallon Clark and Sophie Gorjance.

Elaine Midcoh (a pen name) is a short story writer and an award-winning author of science fiction. She’s a past winner of the Jim Baen Memorial Short Story Award and “The Writers of the Future” contest. Her stories have appeared in the anthologies, “Writers of the Future, Volumes 37 & 39” (Galaxy Press, Nov. 2021 & May, 2023), and “Compelling Science Fiction Short Stories” (Flame Tree Press, Oct. 2022), and in the magazines/literary journals, Escape Pod, Galaxy’s Edge, Daily Science Fiction, Jewish Fiction .net, Flash Fiction Magazine and The Sunlight Press. Before jumping into writing, she worked as a college professor teaching criminal justice and law courses. You can visit her web page at: www.ElaineMidcoh.wordpress.com and can connect with her on Facebook @Elaine Midcoh. She is extremely happy to have her story published in MetaStellar!