Ken’ichi’s white hazmat suit shines like a beacon as he breaks over the ridge, even through all the rain. His gait is slow and uneven. I never expected to see him again.

He’s headed back down into the city. He says there are lights, and he’s right, but I’m not sure they’re what he expects. I don’t want to go, but he insists. I slip a wind-up flashlight and my handgun into the pockets of my own suit, and we walk down the bluff to the rail line.

We don’t talk as we follow the tracks into the outskirts. Ken’ichi’s breathing is labored, his steps increasingly unsteady on the wet pavement. Behind the face mask, his skin is waxy and pale. It’ll be translucent soon, before it sloughs off.

Does he know that it was me? I’m not sure. Does he know that when I panicked and let the death come hissing out, that I ran and hid instead of sounding the alarm?

They know. They know, and they hate me. I can see their contempt in the dark hollows of their eyes, in the way they avoid looking at me for more than a moment, like I’m unworthy of their attention.

Here on the edge of town, they mostly stay inside the buildings, small lights floating by their sides, pale shadows shifting behind the open windows and doors.

It’s only when we get farther into town that their numbers increase and they begin to file into the streets. No longer tied to legs or feet, they drift endlessly down the city blocks, oblivious to the rain, intent on half-remembered tasks, searching for purpose. Occasionally one pauses directly in our path, flanked by their tiny companion flames. Maybe they’re confused by our presence, or maybe they sense Ken’ichi’s condition.

He’s moving slower with each step, but his direction never wavers. We both know where he’s heading: the last place we were happy, with our friends at Hajime’s tachinomiya. The banner still drapes across the front, promising drinks and food and boisterous camaraderie. The winter tarp hadn’t been put out, so the bar’s still open to the street. There were never any tables or chairs, just the counter where we’d all stand after work to share a drink or three or six before catching our separate trains home.

Ken’ichi leans against the counter as I walk behind the bar. “Come here often?” he asks.

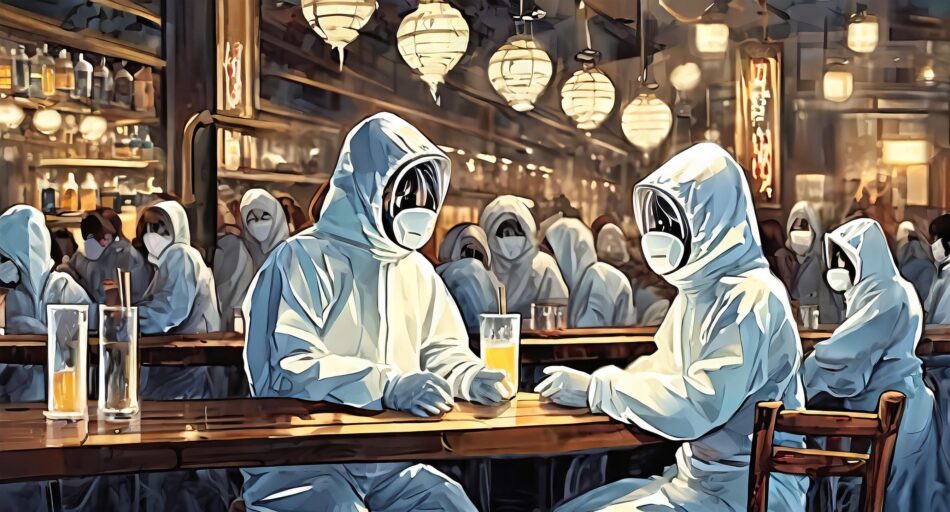

“Not since.” I pull a bottle of sake from the back shelf and fill two glasses. Behind Ken’ichi, a dark-haired crowd is gathering. I’m never sure whether they’re attracted to activity or to me. There are so many that it’s hard for them all to fit into the narrow space of Hajime’s. They glide endlessly in and out and around each other in a legless swirl of silent motion, long hair swaying, their dance barely disturbing the air. A wispy line of dust snakes across the floor beneath them, a fragile shadow of a shadow under all the familiar faces jockeying for position at the counter.

Here’s Kazuhiro, right up front, always at the head of the pack, with his fiancé, Reika, on his arm. Jirō floats a half step back, watching everything, confident in his silence. And everyone loves Daichi, because Daichi loves everyone, big in life and big in spirit. Haruna still hovers at the end of the bar. She’s the only one who’ll look at me, but I can’t look back.

“Why do you stay?” Ken’ichi asks. He lifts his face plate to sip his sake.

I shrug. “Where else would I go?” I toss back my drink and refill both glasses. “Why’d you come back?”

He removes his headgear completely and takes out a crumpled pack of cigarettes. “Where else would I go?” He offers me the pack, but I wave it off. “Suit yourself,” he says, and pulls a bent tube out for himself. There’s a small tear in its side, and he must hold his finger on the hole in order to light it. He chokes on the smoke and coughs for almost a full minute, deep and thick and gummy. “I think you lied,” he finally says.

I don’t answer but pull an ashtray from under the bar and set it in front of him.

“I think you come here every day,” he continues. “I think that’s why you stayed.”

“Why would I do that?”

“I know what happened.” He takes a smaller drag on the cigarette this time and manages to suppress the cough. “I think that’s why they’re still here. They’re waiting for you.”

“To do what?”

“The right thing.”

“Which is?’

He blows a cloud of smoke directly into Kazuhiro’s face. Kazuhiro doesn’t blink. Ken’ichi shrugs and turns back to me. “You have a gun.”

“What, kill myself? There’s nothing honorable in suicide.” I finish my drink. “We should go.”

Ken’ichi shakes his head. “We both know I’m never going to make it back up that bluff.”

“So that’s it.”

“Last call,” he nods and drains his glass.

“I’m sorry.”

“Don’t tell me,” he counters, and waves at the assembled throng. “Tell them.”

I look around the bar at the faces of my friends and the crowd behind them, all the people I never met, thousands of them, floating and waiting. I look at Haruna, and my heart shrivels and withers all over again. “I’m so sorry,” I whisper.

They all turn to stare at me, but in their dark eyes there’s no forgiveness, only anguish.

I put the topper on the sake bottle and place it back on the shelf. “I can’t leave you here,” I tell Ken’ichi.

“Yes, you can,” he replies. “Just leave me the gun.”

I only hesitate for a moment before laying it on the bar. There’s nothing more to say, so I replace my headgear and thread my way out between the patrons. I’m already two blocks away before I hear the gunshot.

Edited by a Fallon Clark and Sophie Gorjance.

Kevin Sandefur is the Capital Projects Accountant for the Champaign Unit 4 School District and is currently pursuing a Bachelor of Applied Studies in Creative Writing at the University of Iowa. His fiction has appeared in The Saturday Evening Post, The Gateway Review, and Pulp Literature.