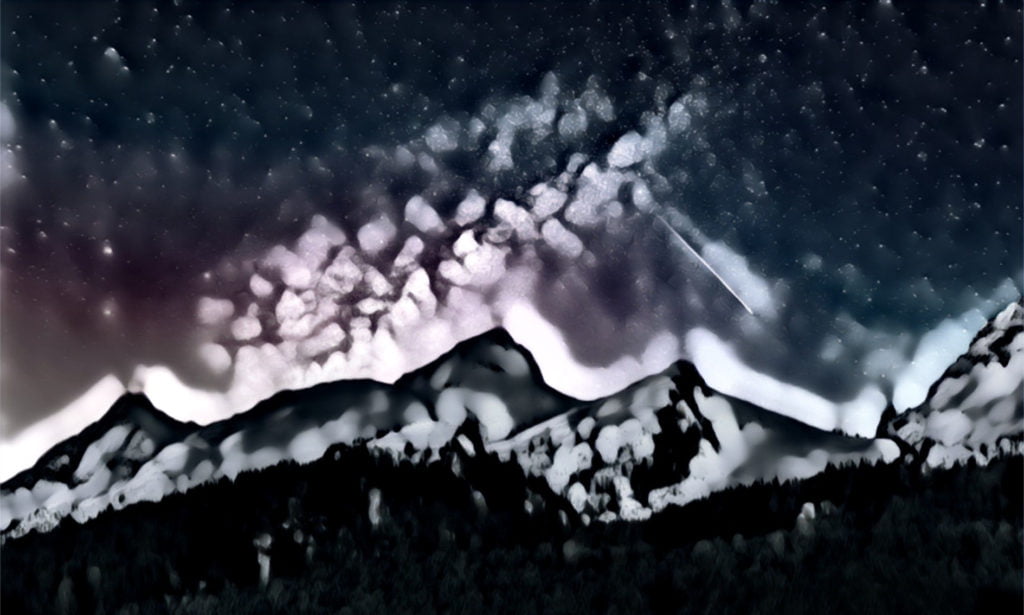

The three stars that walk together: Kuntur, the great condor; Suyuntuy, the black vulture; and Huamán, the falcon star. Father points at them. We are wrapped together on the mountainside, beneath the apu mountain spirit, beneath the Milky Way. In a good year, the three walking stars shine bright. Now they are faint, a sign of the suffering.

Below us, far below, are the lights of Uripa. From west to east flow the refugees, a twinkling of headlights and lamplights. Father says they follow the road to the Sacred Valley, and some further still to the jungle. Wherever they can find a new home. We have a home. It sits below us in the potato fields.

I haven’t seen what the world is running from, and my father won’t tell me. But I have heard what they say in the village. The monsters came from the sky to live in our oceans. Now they tear at the coastlines, dragging cities tumbling to the sea. They wrap around ships and take them under. They make the water rise, all across the world, to drown us slowly.

I have never seen the sea.

I ask father if we will be safe, he says not to worry. He says, “Yara, hija mía, the Andes keep us safe. The apus watch over us. We have all that we need.” He hugs me tighter. He smells of the land and coca leaves, and the aguardiente he buys in plastic bottles without me knowing. But I know. When he drinks, it reminds me of my mother.

The lights of the refugees are a river in the night, flowing from sea to mountains. I imagine the girls and boys down there, walking and walking. I’ve seen the soldiers who guide them, and the soldiers who come to my home. The soldiers carry guns and ask for cheese and olluco. Father says not to talk to them, not to make a sound. But I listen. They say Lima has fallen, Trujillo is gone, and the names of cities I’ve never heard: Guayaquil, Montevideo, Rio de Janeiro. They say we’ll be safe up here, for now.

I sniffle in the cold air. Father strokes my cheek and tugs the shawl tight around us, the shawl my mother weaved. It is decorated with chakanas and hummingbirds. Father puts a finger beneath my chin and tilts my head to the heavens. “Look,” he says, “the Yacana.”

The llama, Yacana, drinks from the Milky Way, the Willkamayu, the great river in the sky that winds through the cosmic sea. Beside the Yacana stands her cria, her baby, mewling and waiting to suckle. They are the dark constellations, the black clouds in the river of stars. And with them, the shepherd who watches the fox, and the fox that eyes the cria. Mach’aqway, the serpent, watches them all, its body a path to the underworld.

Father says I was born under the Yacana, her eyes watching me. Her eyes, he says, are among the brightest. They call them Alpha and Beta Centauri. I know the Yacana well. She walks through the river of stars, becoming blacker as she goes, her baby following behind her. When no one is looking, she comes down to Earth to drink from the oceans. She drinks and drinks, and takes the sadness and pain from the world. Without her, the oceans will overflow and flood the deserts, the jungle and the mountains.

“Does she still drink from the ocean, father?”

My father’s eyes reflect the stars. He looks like Atahualpa.

He says, “I do not know, Yara. But she lives. When she sleeps, the day comes, and the day still comes. And she sheds her wool, black and grey and white and blue, for lucky men to find. Tomorrow we will go look. Maybe we can be lucky.”

I rest my head on my father’s arm. He smells of earth and raw potatoes. The lights below have no end, and the stars above are countless. It’s strange how such pain could come from up there, from something so full and beautiful.

I imagine monsters in the sea, and all the ways to kill them. Because I am not ready to drown.

Tony Dunnell lives in a Peruvian jungle town on the edge of the Amazon rainforest. He is a freelance writer, straying further into fiction with every passing day. You can read more of his writing at TonyDunnell.com.