August, 2026

I returned to my seat, the thunderous applause and cheers still reverberating in the crowded hall. My mother and I shared a hug and friends thumped me on my shoulders. I looked down at the award in my hand, still in shock. Under the soaring holographic rocket were engraved the words “Best Novel” and “Yamei Zhao for Alien Spires, 2026”.

Spires took four years of unrelenting torment to dream, write and edit, and another year to sell. And now it had won the Hugo. Crazy unbelievable. Someone shouted “congratulations!” and pressed a drink into my free hand. Giddy as I was, nevertheless I resolutely put the glass down, still full, onto the damask-covered table.

My mother leaned over, her eyes sparkling with pride, and, raising her voice above the hubbub, said, “Do you know why you love science fiction so much?”

I looked up in surprise, my right hand still gripping the crystal base of my prize. I was about to make some pedantic reply involving vision, alternative realities, and the exploration of change on human society – but something about my mother’s earnest tone stopped me. “No, Mom. Why?”

“Because when I was laid up during my third trimester with you, your father brought me I, Robot to pass the time”.

She looked knowingly at my baby bump.

I laughed. It was as good a theory as any other.

***

November, 1919

Anna stirred the chicken soup carefully, her belly turned sideways to the stove so she could reach the pot. Lately the household chores were becoming a strain. She moved so awkwardly now, and everything took more time to accomplish. But Petrovichi winters were bitterly cold, so hot soup for Judah tonight. And maybe a bissel for herself, although God knew she didn’t have much appetite, at least not for food.

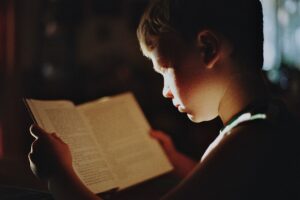

She did have an appetite for stories, and consumed them whenever she had a free moment, although that wasn’t very often. There was laundry to do, and marketing, and cooking and cleaning, and such small repairs as she could manage around the house. But sometimes she had to rest, get off her swollen feet, and then she wanted marvels. Judah brought her books when he could, the old, worn volumes a strange contrast to their tales of future wonders. When rubles were scarce, Judah would instead tell her tales of golems and angels.

She tasted the soup and added a pinch of salt, then sat down to read chapter one of Tsiolkovsky’s Dreams of Earth and Sky.

At dusk Judah came in, shivering from the cold. He gave her a quick peck on the cheek. She placed a bowl of soup in front of him and lowered herself slowly onto the threadbare seat opposite.

“How’s my Annie today?”

“Good. A few more weeks, the midwife says. Quicker for the next one.”

“Next one! What are we going to name this one?”

“If it’s a girl, we’ll name her after my mother. And if it’s a boy, for my father we’ll call him Isaac”.

***

November, 1930

It was raining hard in Brooklyn, the sky a mottled gray, and the streets awash with runoff. Few people had ventured out into the raw day, and none entered the small candy store where Isaac sat reading, hunched as usual, on top of a stack of still-bound newspapers.

His father took advantage of the lull to attend to some business in the tiny back room. The boy, distracted, looked out the window for some moments, but he didn’t see the nebula of swirling leaves or the flapping awning of the appetizing store across the street. His eyes returned to the magazine on his lap.

“Why are you wasting your time with that trash, Isaac?”

Isaac lifted his head once again, his heart pounding. He held the magazine up for his father to see, one hand strategically obscuring part of the title.

“See papa: it’s educational, it’s science,” he pleaded.

His father grunted and began neatening the shelves of sundries, merchandise jumbled by some uncaring customer.

Isaac bent his head once more over the October issue of Science Wonder Stories.

The door swung open to admit a portly woman, and with her a stream of cold, raw air. Isaac pressed back into his corner.

“Good afternoon, Mrs. Sobel,” his father said.

“And the same to you, Mr. Asimov,” the woman replied.

This story previously appeared on Melody Friedenthal.

Edited by Marie Ginga

Melody Friedenthal is a librarian at a public library and a copyeditor for MetaStellar. In her spare time she's the chief bottle-washer for To Tell A Tale Writers' Group and is an affiliate member of the SFWA. Her work has been published in Tales From Shelf 804: an anthology, N3F, Bardsy, MetaStellar, and New Myths. She believes writing is a gateway drug, alpacas are cute, and dark chocolate is heaven.