It’s 1.30am in the morning, and I’m about to watch a duel between magicians. One is a “demonolater”, a word I have never heard before, someone who claims they worship demons and can petition them in return for knowledge or power. The other describes themselves as a “Solomonic magician”, and claims to be able to command demons to do his bidding, as some Jewish and Islamic traditions have believed of King Solomon, who ruled Israel in the 10th century BC.

I first discovered this debate because, in the course of studying 16th century books of magic attributed to Solomon, I had found, to my astonishment, that “Solomonic magic” is still alive and well today, and growing in popularity. Twitter had suggested to me that I might be interested in an account called “Solomonic magic”, and a few clicks later I had found myself immersed in a vast online community of young occultists, tweeting and retweeting the latest theories and controversies, and using TikTok to share their craft.

To my further bemusement, it seemed that the tradition of Solomonic magic had recently faced accusations that its strict and authoritative approach to the command of demons amounted to a form of abuse, akin to domestic violence. As I had made a note in my diary of a public debate that I wanted to attend out of sheer curiosity, it seemed astonishing to be asking myself whether Solomonic magic, the same found in books of necromancy dating back hundreds of years, was on the brink of cancellation in 2021.

At 28, I’m slightly too old to be familiar with the platform Twitch, mostly used for live video streaming, but tonight I’ve managed to get it working for this particular debate. As an atheist, I’m very likely in the minority, though I’m not the only Brit to have turned up in spite of it being such an ungodly hour this side of the pond. The chat box is buzzing as occultists of various stripes arrive to hear the arguments.

My mum would hate this, I can’t help thinking to myself. She didn’t even let me read Harry Potter.

When people ask me what I do, it’s always fun to tell them, “I study magic at Cambridge University.” It’s technically true. I’m researching the representation of magic on the early modern stage, and am interested in the ways in which dangerous, forbidden or “occult” knowledge was theorised by Shakespeare and his contemporaries. My research combines my fascination with the mechanisms of belief with my love of storytelling and the stage. When I’m not researching plays, I’m writing them: I’m an award-winning playwright, whose work has been performed across the UK and abroad.

Suspending disbelief is my forte, but actually believing is something I’ve never been very good at. The history of magic fascinates me because it is a history of people – of human faults and foibles, vanities, hopes and needs – rather than because of any genuine investment in the esoteric. This is why I’m here to listen to articulate and likeable young people across the globe discussing theories of knowledge and the supernatural – beliefs to which I myself cannot subscribe.

Even more astonishingly, these Generation Z occultists, with their substantial followings on Twitter and TikTok, are about to debate a form of magic that lies at the heart of my research into Shakespeare’s England.

This story is part of Conversation Insights

The Insights team generates long-form journalism and is working with academics from different backgrounds who have been engaged in projects to tackle societal and scientific challenges.

The rise of WitchTok

While the most watched TikTok videos may appear asinine to anyone who doesn’t enjoy teenagers lip syncing to popular songs, some surprising subcultures have arisen since the platform’s inception in 2017. One of these is the “WitchTok” community. Videos labelled #WitchTok have so far clocked up an impressive 18.7 billion views.

I accidentally found WitchTok because I had – to my shame, I’ll admit – found it calming to watch compilations of Cottagecore TikTok videos in my breaks during PhD research. Cottagecore is a popular fashion and lifestyle aesthetic that evokes the bucolic idyll of country living. Cottagecore videos are saccharine and safe: jam is preserved, mushrooms are picked, and flowing dresses stream across ripe fields while a girlfriend holds the camera and gentle music plays.

In short, it is pure escapism, and so is WitchTok; creators of WitchToks often also make Cottagecore videos. Yet, where Cottagecore offers hope for a good, green world that just might be baked and planted into existence, WitchTok audaciously skips past the bounds of possibility, and promises supernatural means of making life more bearable.

The abundance of magic on TikTok piqued my interest, representing as it does a new frontier in popular belief. It has also caught the attention of mainstream media. In April 2021, for example, the Financial Times consulted anthropologists and theologians who scrambled to interpret this strange turnout of events. Its author noted with astonishment that #WitchTok had surpassed #Biden by over 2 billion views and is now leading by around 6 billion and counting.

Practical magic

TikTok allows its users to make 15-second video clips, or a string of 15-second clips of no more than 60 seconds in total. This format lends itself to fast-paced, visually appealing content, and this has shaped the kind of magic found on WitchTok. Spells using candles, bottles, crystals and herbs make for snappy and succinct tutorials which can be readily imitated by the viewer.

Interactive WitchToks are particularly popular, usually using tarot cards or pendulum boards,

where a crystal is dangled over a set of words, supposedly swinging over the truth when asked a simple question. By urging the viewer to participate, to “think of a question you want an answer for”, creators are conspicuously gaming TikTok’s algorithm, keeping people watching and encouraging engagement, while claiming that it was supernatural power that drew them to a video.

Brevity is the soul of WitchTok, where complex tarot spreads are abandoned for a one or three card message told to an audience of millions in 30 seconds. Carving a magical symbol into a candle upstages convoluted and expensive ritual magic from more formal, structured esoteric systems, where a single spell can take a day or more.

What, then, are TikTok users looking for in their magical clips of 60 seconds or less? The most common functions of a spell seem to be love, money, healing or revenge, particularly vengeance on behalf of a loved one, whether wronged by a school bully or abusive husband. Magic appeals because life is unfair, and power is a pleasant fantasy. In this regard, WitchTok is no different from any other magical tradition.

Witchtok hunters

The occult subculture is a controversial one, and the witches of TikTok are a particularly powerful magnet for outrage and mockery. They have come under fire from three main types of enemies who appear in turn as caricatures in WitchTok videos.

The first one of these is an interloper who I’ll call “the angry Christian”. When pantomimed in a WitchTok, the angry Christian blazes with furious indignation, railing against the evils of magic, till they are silenced with a sassy retort or threat of a hex. The angry Christian believes in magic, in Satan and in the occult. They simply think you’ll risk your soul if you engage with it. The Christians I grew up with are cut from precisely this cloth.

Less common than the angry Christian but occupying a similarly villainous role is “the smarmy sceptic”, the unbeliever who has no interest in any kind of faith. WitchTok videos often dramatise fantasy conversations with them, imagining ominous retorts: “Don’t believe in curses? Sure! Just give me a lock of your hair then … no?” In some ways the smarmy sceptic is worse than the angry Christian, refusing point blank to be “spiritual” at all. I’m afraid this is probably the category into which I would be placed.

Intriguingly, however, a third opponent has arisen from within the occult community itself. This is what I am calling “the learned magician”, a practitioner who takes the occult seriously as a complex and scholarly pursuit, delighting in the theory, the complexity of rituals, and the broader philosophical implications of their beliefs.

Not quite so TikTok-friendly, they tend to make an occasional appearance when the trends of WitchTok deviate from the logic of a particular magical system, stepping in to correct the new “baby witches” and expressing exasperation with controversies that will sound familiar even to those with no interest in the occult. (Is it cultural appropriation to wear an evil eye pendant? Does calling for discipline in magical ritual equate to a form of fascism?)

Some learned magicians are attempting to bridge the gap. Gen-Z occultist Georgina Rose or “Da’at Darling” – who has convened the debate between the demonolater and Solomonic mage to which I am about to listen – puts out a prolific array of content ranging from introductory YouTube lectures to witty tweets and TikToks.

Upset by the “rise of anti-intellectualism in Generation-Z heavy online occult spaces”, she responded, appropriately, with a successful TikTok hashtag: #DefendOccultBooks. Perhaps not an outright “enemy” of Witchtok, after all – as “Da’at Darling” puts it, “it is important to reach this platform, so new practitioners can have good information on the occult” – the learned magician is still, at best, tolerant of the trends of TikTok spirituality.

Here, then, is a new theatre of ideas where innovative technology has not quelled ancient magical practices but has advanced them, giving rise to new forms of faith and schism. If the unbelieving reader is asking themselves how a new age of occultism has arisen in a supposedly enlightened modern age, when surely the tech-literate young know better than to return to ancient superstition, they need look no further than a parallel series of events in Shakespeare’s England. This was a time when innovations in technology and culture served to reinvent and energise ancient magical beliefs.

The occult renaissance

In medieval England, getting your hands on a book of magic was a tricky business. Prior to the invention of the printing press, handwritten texts were passed around in manuscript form between those lucky enough to have been taught how to read. Costly and time-consuming, the production of a book was simply not worth the effort unless the contents truly mattered.

In spite of this, from the mid-13th century onwards, a series of treatises that dealt with occult knowledge were translated into Latin and various European languages, slipping covertly between the personal libraries of wealthy men. If the Renaissance can be characterised more widely as a period of translation of classical wisdom, so too was it an era when occult “wisdom” began to circulate more widely than before.

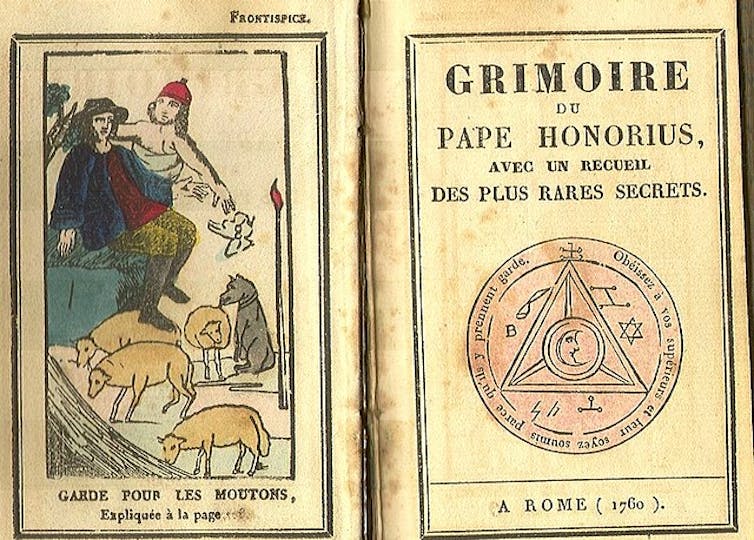

Books of magic, or “grimoires”, a word which derives from the French grammaire, promised, like ordinary school grammars, to teach the reader the rudiments of a new language, though this was the language of spell-making and devil-raising. Grimoires were frequently attributed to famous men of esoteric learning, and the wise king Solomon in particular appealed to Christian readers. If Solomon had authored such a text, could not the wise Christian reader likewise practice the occult without endangering his soul?

Rumour of the grimoires and their grim rituals would circulate widely throughout the medieval era while the actual, often comparatively bland contents, remained obscure.

The occult reformation

The introduction of printing press technology to Europe in the 15th century revolutionised the speed and scale by which all texts could be produced. It was the printing press which facilitated the Protestant Reformation, and it was also the printing press which was responsible for the introduction of the occult grimoires to a larger audience than ever before.

Surprisingly, this occult reformation was enacted not by magicians themselves, but by a series of sceptics who believed that, by revealing in print the content of infamous esoteric manuscripts, they could expose them to the ridicule that they deserved.

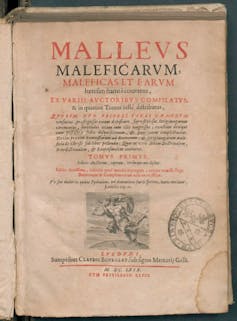

Dutch scholar Johann Weyer’s Latin treatise De Praestigiis Daemonum or “On the Tricks of Demons” was published in 1563. It was one of the first great sceptical works debunking magic, criticising notorious witch hunting manuals like the Malleus Maleficarum and, indeed, successfully curbing some of the continental witch trials. Weyer’s work had a huge influence on one Englishman in particular, Reginald Scot, who borrowed from it in his own book, The Discovery of Witchcraft, first published in 1584.

Scot’s The Discovery is a thrilling exposé of both the folk magic practised by witches and the “learned” magic found in grimoires, particularly those attributed to Solomon. Weyer had included, as an appendix to De Praestigiis Daemonum, a direct translation of a Solomonic grimoire which listed the names and ranks of various demons, and how a magician might go about conjuring and commanding them as, supposedly, could Solomon.

Scot “Englished” much of this appendix for his book, concluding scathingly: “He that can be perswaded that these things are true … may soone be brought to beleeve that the moone is made of green cheese.”

Though by no means an atheist – nobody was, at least not openly, in the 1500s – Scot was certainly a smarmy sceptic, and The Discovery shares the exasperated horror of Richard Dawkin’s The God Delusion (2006) at the excesses of superstition and belief. Joined by George Gifford’s A discourse of the Subtill Practices of Deuilles by Vvitches and Sorcerers by which Men are and Haue Bin Greatly Deluded (1587) and Henry Howard’s A Defensatiue Against the Poyson of Supposed Prophesies (1583), Scot’s treatise seemed to ride the crest of a new wave of scepticism concerning the whole project of magic in general.

Surely the genie was out of the bottle (or demon out of the brazen bowl, as the Solomonic grimoires would describe it). Now that occult beliefs had been so thoroughly exposed and ridiculed, how could they possibly survive?

King James and the witches

In 1597, King James VI of Scotland, who would inherit the English throne in 1603, published an extraordinary treatise: Daemonologie. The book was not, as the name might suggest, a grimoire-like guide to the conjuration of demons, but rather a serious study of demonic power and the harm it could inflict. King James did not accept the suggestion that any man, even if he was as wise as Solomon, could seriously practise magic without risk to his soul. Nor did he believe, as the smarmy sceptics did, that there was no real threat whatsoever.

James was an angry Christian, a man who believed, sincerely, in the power of the occult and felt duty-bound to protect his people from it in all its forms. He had nothing but contempt for the likes of Scot, whom he regarded, in much the same way as a modern Christian fundamentalist might regard an unbeliever, as a dangerous mocker who did the Devil’s work for him by dismissing the real threat that magic posed.

Even worse, Scot and his fellows had inadvertently introduced into printed English, for the first time, the detail of dangerous grimoire magic which had formerly reached only limited circulation. While it is a myth that James ordered copies of The Discovery to be burned, extracts from the text were indeed consigned to the fire during the witch trials of the 17th century, when sections were found, freed from their original sceptical context, in the documents of those accused of witchcraft.

One devil too many

My PhD looks specifically at the fallout of this fascinating cultural clash in the work of the early modern dramatists, and I am particularly interested in the overlooked presence of Solomon in these debates. Most famously, it was Marlowe’s Doctor Faustus which sparked a vogue for plays that dealt with the question of the learned magician.

Written in around 1588, Doctor Faustus drew on Scot’s The Discovery in its representation of magic, yet discarded its dismissive tone. Faustus succeeds in summoning the demon Mephistopheles, and signs away his soul in a contract written with his own blood in return for 24 years of power. After wasting his time on petty vengeances, greed and lust, Faustus is finally sent to hell.

Rumour circulated that an extra devil had been seen on stage during the play, a fact which the Puritan William Prynne would gleefully repeat as proof of the evils of theatre in his Histriomastix, 1632. Magicians who both did and did not achieve their hoped-for Solomonic command of occult forces would populate the English stage for decades.

Scot and the sceptics had indeed laid bare the detail of occult belief, and their work was highly influential, but it had precisely the opposite of their desired effect. Advances in technology, accessible English translations and an entertainment industry hungry for a good story had conspired to democratise magic. The process they unwittingly began continues today on TikTok and elsewhere.

Solomon on trial

It’s a strange truth that grimoire magic is more widely available in 2021 than ever before, and that it is the internet which has popularised exactly the same material that was hidden in a handful of libraries for the first few hundred years of its presence in Europe.

With the debate about the ethics of Solomonic magic underway on Twitch, I hardly dare imagine Scot’s horror, much less King James’s, to hear phrases like “pro-demon rights” from a young person describing themselves as a “demonolater” and “magic is the scientific study of conversations with spiritual beings” from a self-professed “Solomonic mage”.

The latter has done a good job of persuading the Twitch stream that commanding demons is not inherently disrespectful, though a poorly-judged comparison between the authority of the magician and that of the policeman sparks momentary indignation in the chat.

Nevertheless, the debate is civil and ends with discussions of new online editions of the rare grimoires. It seems the magical incarnation of King Solomon will live to exorcise another day, and I can’t say I’m surprised. The historical inability of sceptical dismissals and technological advances to do anything other than encourage belief in magic has persuaded me that the fundamentalists are right in one respect: speak of the devil and he shall appear – and that goes for TikTok too.

For you: more from our Insights series:

- The Prestige: the real-life warring Victorian magicians who inspired the film

- James McCune Smith: new discovery reveals how first African American doctor fought for women’s rights in Glasgow

- Climate crisis: how science fiction’s hopes and fears can inspire humanity’s response

To hear about new Insights articles, join the hundreds of thousands of people who value The Conversation’s evidence-based news. Subscribe to our newsletter.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article.

Rebekah King is a PhD student at the University of Cambridge writing a thesis on the figure of King Solomon in early modern drama. Rebekah has two masters' degrees: an MSt in English 1550-1700 from the University of Oxford, and the practice-led MA in Shakespeare and Creativity from the Shakespeare Institute, taught jointly with the Royal Shakespeare Company.