So you’ve finished your draft manuscript but you’re worried the story is a little bloated?

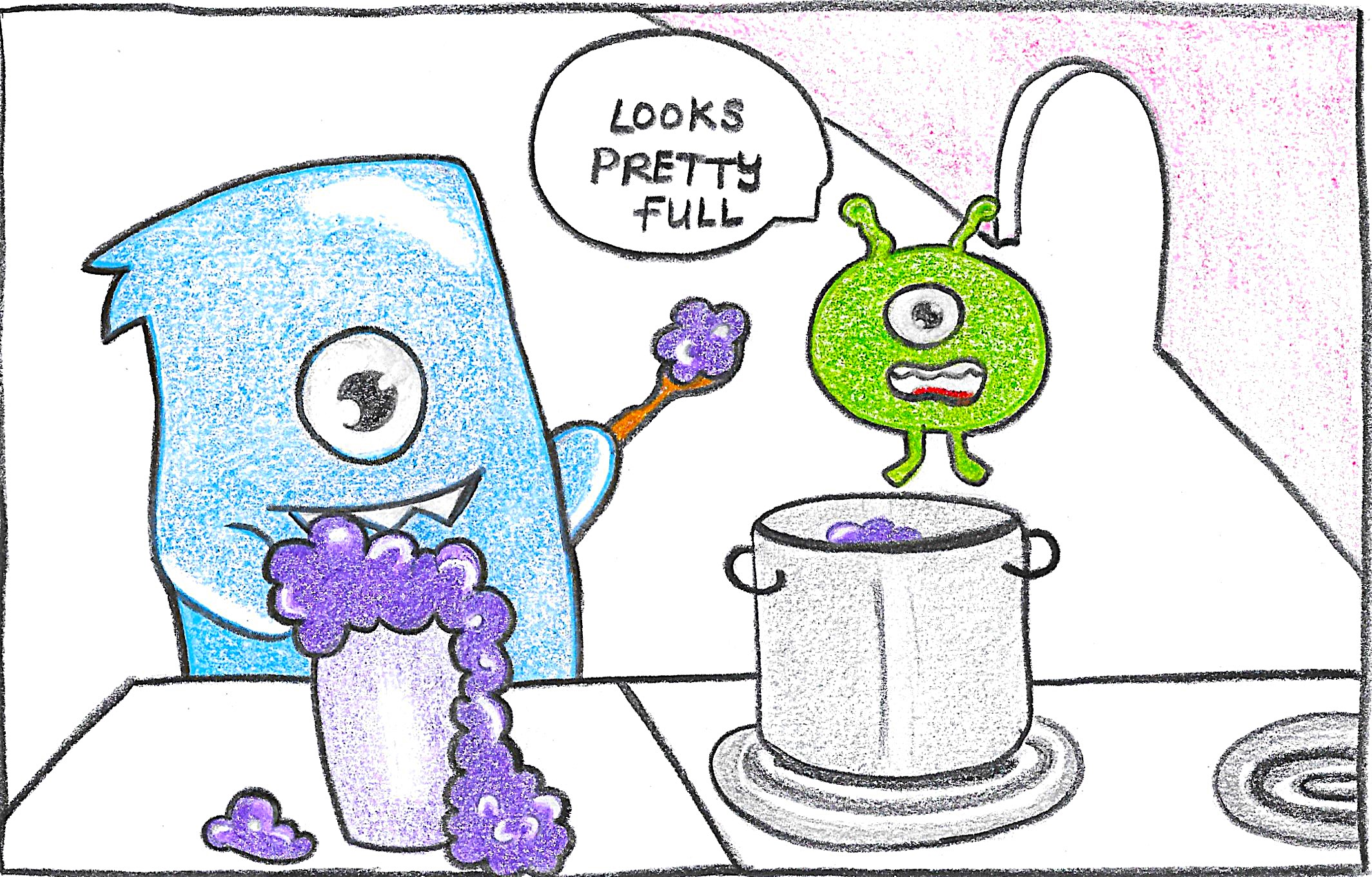

Like that aunt who shows up in stretchy pants for every family get-together, your manuscript is positively stuffed to its bursting point. Unlike that aunt, though, your manuscript holds onto its bloat, repels would-be readers with its magnitude, because it can’t very well release a diaphragmatic burp and ease the pressure.

No, you, fine writer, will need to manually add a pressure-release valve by editing out the bloat, paring back the book to its essence and message, and trusting your readers handle the rest.

A couple weeks ago, I shared Word Count by Genre: A Guide for Novelists, which provides a high-level target for the word count of your novel based on genre expectations and reading age group.

But figuring out how to de-bloat a manuscript, where to add that pressure-relief value, figuring out what to cut while retaining the foundations and leaving intact the soul of your story, is the rub: Cut from the wrong spot and the theme may fall apart, or your characters may become little more than talking heads, or your readers may get lost in spacetime.

In this article, I’ll share two major ways to edit a bloated manuscript for your readers, so its magnitude stops repelling and begins attracting.

Where does the story truly begin?

Often, when reading through a draft manuscript for the first time, one major bloat-factor sticks out: The story starts in the wrong spot.

Starting the story in the wrong spot is a very common development issue, especially for new authors and those seasoned authors who are moving to new genres. A manuscript that begins in the wrong spot can put off agents, editors, and readers, which means your book won’t sell.

However, there are often many points at which your story could begin, so how do you choose? What makes one starting spot better than others?

Mystery novels often answer this question best: Start the story when the action begins.

Earlier this year, I read The Witch Elm by Tana French; more recently, Girls Like Us by Cristina Alger. Both are mystery novels. Both are traditionally published by The Big Five. Both begin on page one with a change or intrigue of some kind.

In The Witch Elm, readers begin to understand a little about the story when French writes, “And of course there was the Ivy House. I don’t think anyone could convince me, even now, that I was anything other than lucky to have the Ivy House.”

Of course, the Ivy House becomes the crime story’s epicenter, and in the opening chapter, the protagonist is beaten nearly to death in a robbery gone wrong and ends up at the Ivy House to convalesce.

French even calls out the story beginning problem when she says, through the protagonist, “That night. I know there are an infinite number of places to begin any story, and I’m well aware that everyone else involved in this one would take issue with my choice—I can just see the wry lift at the corner of Susanna’s mouth, hear Leon’s snort of pure derision. But I can’t help it; for me it all goes back to that night . . . .”

In Girls Like Us, Alger kills off the protagonist’s father before the story begins, forcing her protagonist to travel back to her childhood home for a funeral just in time for a horrific crime to occur.

Cleverly, Alger alludes to the coming crime through an innocuous comment about the weather, of all things, which sets an anticipatory tone for the opening of the novel: “It’s a calm day. They say a storm is coming, but for now, the sky is cloudless . . . . The men look on as my father’s ashes blow away on the wind.”

While the events loosely described in first chapters of The Witch Elm and Girls Like Us change something for their respective protagonists, the inciting incidents happen just a bit later and more formally jettison the protagonists into their stories.

- In The Witch Elm, the inciting incident is a cancer diagnosis and a frail uncle who needs live-in help. And the protagonist, who needs intense rehabilitative care following his bloody beating, is just the right person to take a long sabbatical out in the country.

- In Girls Like Us, the inciting incident is the discovery of a body near the wealthiest homes on the island, an investigation the protagonist happens to become wrapped in expressly because she’s an FBI agent who just happens to be on the island paying respects to her father (who was a cop) when the young woman was murdered.

It’s easy to begin your story in the wrong spot because there were things you needed to know about the protagonist’s daily life before mucking it up. But there’s a good chance your reader doesn’t need all the details you’ve painstakingly written into your early draft.

In fact, for the last several manuscripts I’ve read and assessed for development, cutting several opening chapters has been the running recommendation so the readers get to the inciting incident just a bit faster and your novel holds their attention that much longer.

If your manuscript is bloated, start the story just one event before the inciting incident, cutting everything that came before, so your protagonist can be in the right place at the right time.

From whom do readers need to hear?

If you haven’t read The Witch Elm or Girls Like Us, know that both stories have but a single narrator. There are no point-of-view shifts or additional perspective characters introduced, which is common in mysteries so as not to divulge too much information to the reader such that they unravel the mystery before the characters even have a chance to realize they’re in a mystery.

Having multiple perspective characters in novels makes sense when the narrators are peripheral to the events, observing and interacting with the hero without actually being the hero.

High fantasy stories often include multiple perspective characters, for example, because it’s the combined goings on of the various characters which create the stories’ messages. And multiple perspectives work well when the characters can’t possibly share experiences because they’re in different locations, or speak different languages, or exist at different times in history.

One novel that comes to mind is All The Light We Cannot See by Anthony Doerr, the perspectives of which move back and forth between a French blind girl and a German orphan boy who’s been handpicked for the war effort.

The two protagonists are, figuratively or literally, battered by World War II, and both live in different towns at the story’s opening. The characters never cross paths except toward the end when, briefly, they meet and part again. Yet, their two perspectives—one of a soldier working for the axis powers, one of an allied operative—showcase the breadth and depth of the war experience.

Yet, I’ve also read and assessed plenty of novels that use far too many perspective voices, such that the true hero becomes lost, or certain perspectives are skimmed simply because they don’t move the story enough.

For many stories, especially contemporary stories, the reader only needs one narrator, one perspective through which to experience the story events, one character to follow and learn from, one character to which to compare themselves and what they would have done were they in the character’s shoes.

If your manuscript is bloated and you have multiple perspective characters, one quick way to add a pressure-relief valve is to cull the perspective chapters of one or more characters.

TL;DR: De-bloating your story begins with assessment

Editing a bloated manuscript starts with careful assessment of major development factors, including starting the story in the right place and making sure the perspective characters chosen are appropriate for relaying necessary information to your readers.

If you still find your manuscript is larger than you’d like but you’ve already overhauled the big-picture stuff, you may find a careful language edit may help you tuck and tighten.

Check out these related articles to help you wrangle your language for concision and clarity:

And for more big-picture analysis, check out these articles to help you conceptualize:

- Telling the Two-Sided Story

- Story is Goal, Motivation, Conflict

- Plot Turning Points and Story Development

- Or check out the POV Deep Dive series.

So, how do you de-bloat your manuscript? Share your tips below!

Happy writing!

<3 Fal

Prefer video?

Come hang with me on the MetaStellar channel:

Fallon Clark is a story development coach and editor with more than a decade of experience in communications, project management, writing, and editing. She provides story development and revision services to independent and hybrid publishers and authors spanning genres and styles. And in 2018, she had the joy of seeing Forever My Girl, one of her earliest book projects, on the big screen. Fallon’s writing has been published in Flash Fiction Magazine and The MicroZine. Find her online at FallonClarkBooks.Substack.com, or connect with her on LinkedIn or Substack.