Imagine you read a book. You commit details of the book to memory and ruminate on the ideas contained in it.

Somebody then asks you a question about the book. You provide them with a written response.

Would you be surprised if the author of the book tried to sue you for copyright infringement?

OpenAI is facing exactly this situation.

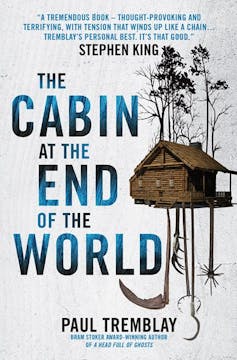

Authors Mona Awad (Bunny, 13 Ways of Looking at a Fat Girl) and Paul Tremblay (The Cabin at the End of the World), filed a lawsuit against OpenAI last week, claiming the books were used to train ChatGPT, its artificial intelligence software, without their consent.

It is the first lawsuit against ChatGPT that concerns copyright, The Guardian reported.

The only difference from the scenario I’ve outlined is that instead of a human reading a book, OpenAI is accused of allowing its AI program to copy a book to its internal database and train on it.

What’s the lawsuit’s chance of success?

OpenAI is a large language model (LLM). These LLMs train on data in the form of written works in order to provide natural language responses to prompts.

The basis of the lawsuit is that OpenAI trained itself on their novels and produced accurate summaries of their works when prompted.

Notably, the lawsuit does not specify which specific parts of Awad and Tremblay’s novels have been unlawfully copied and reproduced in the summaries.

The lawsuit alleges OpenAI uses “shadow libraries” that illegally publish thousands of copyrighted works (using torrent systems). Their claim is based on a 2020 paper by OpenAI that reveals 15 percent of their training dataset comes from “two internet-based books corpora.”

But the lawsuit faces some immediate hurdles.

The litigants will need to prove that OpenAI most likely copied their works. They will also need to demonstrate the likelihood of some economic loss. Crucially, copyright protection does not extend to ideas.

Copyright protection is limited to written expression. And though copying something to a database might be an act of infringement, that act alone is unlikely to cause significant harm to the economic interests of the authors.

The real danger is that OpenAI can do some of the things human authors can do.

How does Australian law apply?

OpenAI is just the first generation of what this technology looks like. No doubt, many authors (and other creative producers) are starting to wonder what will happen when OpenAI and similar technologies evolve.

Moore’s Law, a calculation that estimates the capacity of digital technology doubles roughly every two years, suggests the rate of this development might be exponential.

What would happen if a similar claim was raised in Australia? Would our fair dealing laws step in and protect the development of technology – or would our law side with the authors?

The United States has the doctrine of fair use in its copyright laws.

In the past, fair use has been used to draw a balance between new technologies and established copyright interests. The Sony video cassette recorder case is a famous example.

In the Sony case, a majority of the US Supreme Court permitted homeowners to record their favorite television shows and watch them later, so long as they didn’t keep the recordings. (By comparison, Australia didn’t legalize this until 2006.)

Fair use also allowed the rap group 2-Live Crew to radically rework and parody Roy Orbison’s song Pretty Woman.

Australia has effectively put the essence of some fair use decisions into its Copyright Act. The Australian Copyright Act contains provisions on time-shifting and fair dealing for parody.

Yet, Australia has repeatedly declined to house fair use within its law.

Instead, we rely upon its unwieldy cousin, known as the doctrine of fair dealing. A claim like the one Mona Awad and Paul Tremblay are making against OpenAI would likely fail in Australia.

Ideas are not protected

Like the United States, Australian law protects tangible expression, but not ideas. People need to be free to use ideas in subsequent works.

Much the same logic should apply to large-language models such as OpenAI.

And a formidable barrier emerges in the bedrock ideas of copyright law.

Copyright was conceived and refined in an era when writing and copying were done by human beings. This means the fundamental concepts within the law relating to subsistence (proving a work’s continued existence), infringement and exceptions are human-centric.

This is quite a mountain to climb in any copyright litigation. If a human actor has not committed an act of infringement, it might be hard to find another human liable – even though an author might feel aggrieved.

Nevertheless, the base problem is that Australian law does not house an open-ended legal rule like fair use, which can draw a fine balance between technology and authors.

And we are yet to have the policy debate here about how we will manage the looming conflict between rapidly advancing technologies and authors who depend on their writing for their livelihoods.

The OpenAI litigation might well fail. But it is just the first salvo in a major AI-driven groundshift in copyright.![]()

This article is republished from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the original article here.

Dilan Thampapillai is an associate professor at the University of New South Wales in Sydney, Australia. He has significant expertise in artificial intelligence, copyright and contract law and previously advised the Australian government on treaties, copyright, and commercial matters.